If you don’t work in the health-care system, and maybe even if you do, but you don’t work in the OR, IOM Technologist is likely one of those jobs you don’t know exists.

As an Intra-Operative Neurosurgical Monitoring Technologist, or neuromonitorist for short, Kristine Pederson ensures a patient’s nervous system remains functional during complex and sometimes high-risk spinal and brain surgeries. The goal: to prevent potential damage to the brain and spinal cord which could result in stroke or even paralysis.

Neuromonitorists are a rare professional specialty in Canada, particularly in Manitoba.

“There are only two of us in the province actually, myself and Dr, Marshall Wilkinson, and we both work out of HSC, so I would definitely call us a tiny, understaffed team,” laughs Kristine. “Another city hospital has been wanting to use neuromonitoring for certain high-risk cardiac surgeries for over a decade, but we don’t have nearly enough staff to cover two centres.”

Kristine started her post-secondary journey by completing a Bachelor’s degree in Physiology & Pharmacology at the University of Saskatchewan, and then decided to pursue the two-year diploma in Electroneurophysiology at BCIT in Vancouver.

“When you complete this program, you can become an electroencephalography technologist who performs EEGs (brain scans) to assess for seizure disorders like epilepsy; you can specialize in performing sleep studies, or you can work in a nerve conduction clinic to diagnose degenerative and peripheral nerve disorders. Once I found out I could combine all of these different tests together and work in an operating room, I chose that path.”

Kristine has been at HSC for eight years working as part of a multi-disciplinary team supporting neurosurgeons and orthopaedic spine surgeons. She also completed a two-year program in Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring through the Michener Institute concurrent with her on-the-job training.

“While they’re under anaesthesia, patients obviously can’t express things like abnormal sensations or weakness, so it’s our role to monitor the body systems during surgery and sort of act as the patient’s voice while they sleep.”

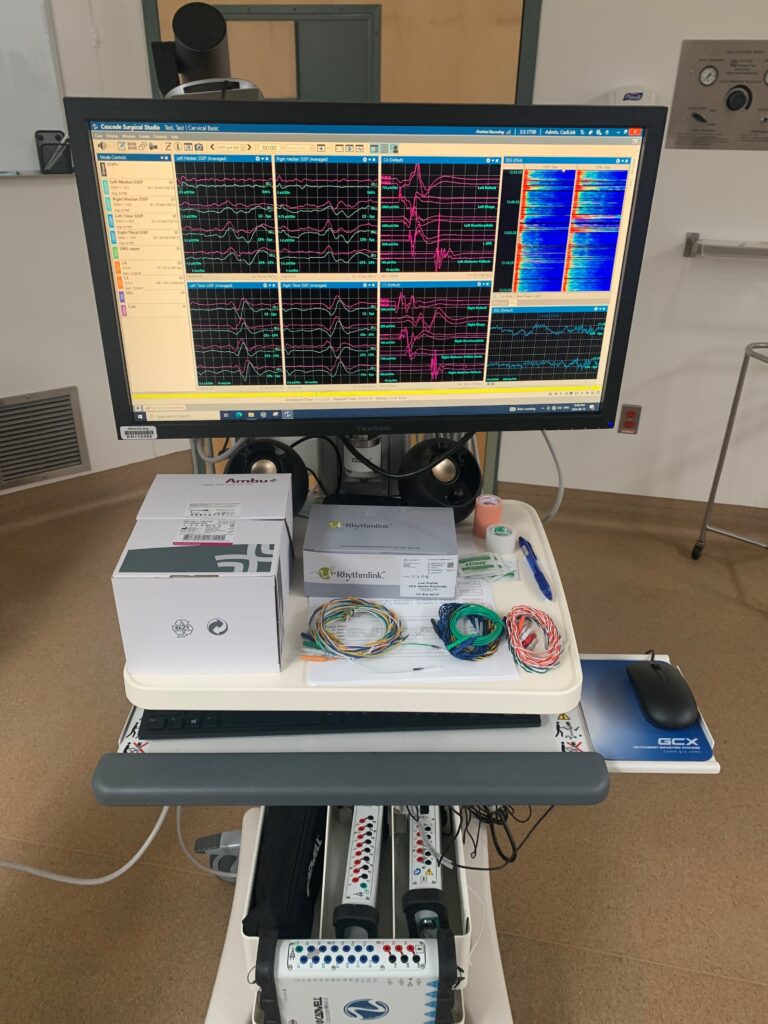

Kristine consults directly with surgeons in advance to collect information about the patient, their diagnosis and the surgical plan, then places electrodes on the patient’s body to enable her to monitor motor and sensory function. She then reads the ‘squiggly lines’ on the computer screen throughout the surgery. If there is a change in the patient’s function, she alerts the surgeon, who can often reverse the last surgical maneuver before permanent damage occurs.

“It’s amazing how many things are plugged in and connected to a patient during an operation. It’s very crowded in an OR with all the equipment and monitoring going on, from EKG and ventilation to neurophysiological. Any time there is a concern, the entire team – surgical, anesthesia, nursing and neuromonitoring – works together to make sure the patient is stable and safe.”

The IOM team assists in a wide spectrum of surgeries with the majority being spinal, and also including brainstem and cranial nerve surgeries, brain tumor resections and neurovascular procedures.

“The reality is that it can be anywhere from really boring to really stressful, depending on the surgery, but even uneventful operations require continuous monitoring. We can’t bounce back and forth between ORs to accommodate multiple surgeries, because a patient’s situation can change at any moment.”

Example day in the life of a neuromonitorist: Brain tumor resection

6:45 AM – Feed cat

7:15 AM – Arrive at work

7:30 AM – Conversation with surgeon and anesthesiologist regarding patient’s clinical status, tumor location, anatomy at risk, anesthetic considerations, and plans for neuromonitoring.

8:00 AM – Apply electrodes to anesthetized patient.

8:45 AM – Leave OR; inhale a coffee during surgical exposure.

9:15 AM – Back to OR; stare at squiggly lines; try to look relaxed so surgeon doesn’t get worried.

10:00 AM – Assist surgeon in creating a ‘map’ of eloquent brain areas so nothing functional is resected.

10:15 AM to ? – Continue monitoring squiggly lines and updating ‘brain map’ as resection continues. Alert OR team if anything changes and work together to reverse the change.

End of surgery (could be any time) – Remove electrodes and clean equipment.

After work – Go home; eat dinner; relax; feed cat again; bed.

Typically, Kristine and Marshall each have one OR booked per day, with surgeries often scheduled for the entire day.

“Once the surgery begins, we aren’t able to leave for lunch breaks, or even bathroom breaks, unless someone takes over monitoring. With our current staffing shortage, this means we’re often in the OR for many hours without relief, and sometimes, surgeries can go unexpectedly late due to unforeseen circumstances. If we have to stay late into the night to finish a surgery, we still have to be back bright and early the next morning to start another case because there is nobody to cover the scheduled ORs.”

According to Kristine, sometimes a surgery may go ahead without neuromonitoring if the physician feels the risks of delaying it until a neuromonitorist is available outweigh the risks of proceeding without neuromonitoring. Unfortunately, sometimes, surgeries have to be bumped because of a lack of staffing, and that’s disappointing to Kristine.

“This is obviously never what we want. We want patients scheduled for surgery to undergo their procedure in a timely fashion, and for the procedure to happen in the safest way possible and leading to the best possible outcomes. It’s frustrating for the whole team knowing that surgeries are happening without neuromonitoring because the patient isn’t able to wait for our schedule to have an opening.”

Kristine loves her job but she’s concerned. This year, the Government of Manitoba announced it would increase the number of spinal surgeries by 50 per cent, but that will be difficult without adding to the IOM Technologists team. Ideally, with the planned increase in spine slates, HSC would have six neuromonitorists, which would mean they could support all surgeries and have appropriate back-up coverage.

“There’s no doubt we work hard here in Manitoba. In other jurisdictions, neuromonitorists earn better wages and often have a lesser level of responsibility. At HSC, with our current staffing situation, each neuromonitorist must be an expert, solely responsible and able to run their own OR from beginning to end. Two technologists have been recruited to join our team in the past year and they each only lasted weeks before leaving for other opportunities in other jurisdictions.”

Outside of work, Kristine loves animals and gives of her time to Manitoba Mutts Dog Rescue. She fosters cats, attends adoption fairs, supports those who adopt and raises funds to help the rescue. She loves to cook, finds peace in her garden and spends most of her vacation time visiting family and friends scattered all across Canada.

“I have a lot of really positive things in my life and work is definitely one of them. I would just like to see some investments in our team so we can support the spinal surgery expansion and make sure that all surgical patients get the best care they deserve.”